Authors: Tomás Barrio y Alvina Huor

A recent study opens the door to faster, more accessible and accurate diagnoses of neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson's disease, Lewy body dementia and multiple system atrophy.

Diagnosing diseases such as Parkinson's disease or Lewy body dementia with certainty remains a major challenge in medical practice. These conditions, known as synucleinopathies because they share an alteration of a protein called alpha-synuclein, are currently diagnosed based on clinical symptoms and signs. This not only can lead to errors, as other diseases present similar symptoms, but it can also delay diagnosis, by which time neurological damage is already considerable.

A new study published in the journal Acta Neuropathologica Communications (you can access the original article here) proposes an innovative tool that could change this landscape. Researchers have developed a laboratory technique that allows the detection of the ‘pathological’ form of alpha-synuclein—that is, the form involved in these diseases—in different types of samples from the human body, such as skin, nasal mucosa, and even urine.

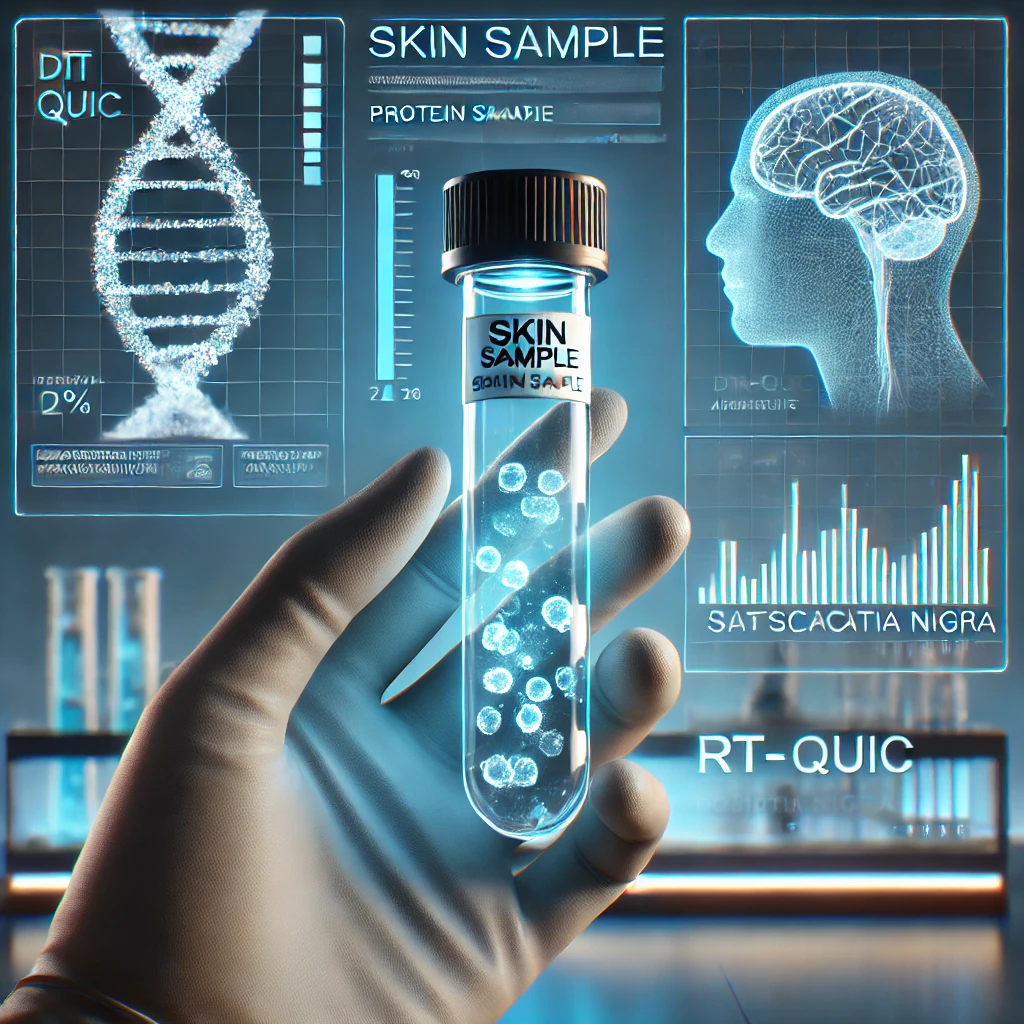

The technique, called RT-QuIC, is already used to diagnose other neurodegenerative diseases such as prion diseases (e.g., Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease). In this new study, it has been adapted to identify altered alpha-synuclein, which acts as a kind of ‘seed’ that spreads the disease in the brain, much like the prions that cause Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease or fatal familial insomnia.

The results are very promising. The technique was able to detect the presence of the pathological protein in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), a fluid that surrounds the brain and is obtained through lumbar puncture, with 82% sensitivity (percentage of samples with an accurate diagnosis of Parkinson's disease that the technique revealed as positive). But what is most innovative is that it also worked with much more accessible samples.

For example, in small skin biopsies obtained from the neck using a minimally invasive puncture, the test achieved 96% accuracy, making it a particularly interesting option for the future. Samples from the olfactory mucosa, taken using a nasal swab, also performed reasonably well (74% accuracy), although the authors note that sample processing has a significant influence on the result, so there is room for improvement.

Other samples that are even easier to obtain, such as saliva and urine, showed more limited results. The protein could not be detected in saliva, and although it was found in some cases in urine, sensitivity was low (22%). Even so, this suggests that, with further refinement of the technique, they could become useful as part of a combined panel of biomarkers or disease indicators.

This study represents an important step forward towards earlier, simpler and more reliable diagnosis of synucleinopathies. Detecting these diseases before serious symptoms appear would allow treatment to be started earlier, improving patients' quality of life and facilitating the design of clinical trials for new therapies.

Researchers, healthcare professionals and patient associations will closely monitor these advances, which bring us ever closer to the possibility of reliably detecting these diseases with a simple sample, without the need for invasive procedures.